How Tracksmith Built a Cult Running Brand that's Grown 280% over 3 Years

How long form content and love of the sport is building a brand for the long run

👋 Hi, I'm Amanda. I'm a brand strategist and fractional CMO. I help founder-led businesses turn belief into brand—and brand into a strategic asset that works as hard as you do. I share weekly deep dives with actionable advice on brand building—plus interviews with the people in the trenches. I also work 1:1 with founders and teams. Book a chat here.

TLDR 📓

To co-opt the words of Lance Armstrong, Tracksmith is not about the gear. It’s about the story. It’s about belonging. Tracksmith shows us that businesses that invest in brand from the beginning build compounding interest that gives them an outsized ability to find, win, and keep more customers.

➡️ This will inspire you if you’re a B2C company: Leveraging heritage, building community-driven loyalty programs, selling a lifestyle (not just a product).

Today

Redefining elite: How Tracksmith makes exclusivity a power move

How solo runners find community in Tracksmith’s brand

Tracksmith’s secret sauce: slow growth, stunning content

3 tips for brand builders

If you’re a running nerd, like me, you’ll know that Boston Athletic Association, the governing body of the Boston Marathon, recently announced stringent entry requirements for next spring’s marathon.

Some background: The Boston Marathon is a race that requires participants to qualify, and the field gets faster every year.

This is where Tracksmith come in: a relative newcomer to the running apparel scene.

Tracksmith came under fire for a social media post (since deleted) about a singlet reserved only for Boston Marathon participants. It sparked…a LOT of ire.

While Tracksmith has been making Boston merch since 2015, the post played on the exclusive nature of the race (qualifiers only) and introduced a new constraint - only runners who’d qualified for and registered for the race in 2024 could purchase it (this is the runner version of ‘you can’t sit with us’).

“We wanted to make sure it’s something special for qualifiers only,” the post read. “Harder to get, harder to earn.”

The post racked up 1500 comments criticizing Trackmith’s elitist brand.

How did they get here?

Let’s rewind the tape 🎥.

What is it?

Tracksmith, founded in 2014, is a running apparel brand for serious runners. It was created by Luke Scheybeler and Matt Taylor, emphasizing running culture and New England heritage.

If it sounds vaguely familiar, that's because it is. Scheybeler, brand and creative director, is also a co-founder of Rapha.

It’s not even 10 years old, but it feels like it’s been around forever. In a world where DTC brands can feel a bit soulless (slimy, even?!), Tracksmith stands out as a category disruptor. Like most built-to-last brands, they’ve invested in the brand from the beginning.

The seeds for Tracksmith came from a frustration with the way established running brands ignored the core runner, watering down their messaging to appeal to a broader fitness/athleisure base. So in establishing the framework for Tracksmith, it was important to speak to that runner who’d been left behind.

These are “serious” athletes, in that they’re committed to a lifestyle of training and racing, and everything that goes with it. At the same time, these are not professional runners; they fit their training alongside full time jobs, families and other personal commitments. Running has an incredible history of amateurism and our aim is to treat running with the respect it deserves and offer runners products and experiences that support their commitment to getting faster.

This is the story of Tracksmith.

The brand positioning: Aspirational amateurism

To understand Tracksmith’s brand of aspirational amateurism, we need to take a detour to the 70s.

Back in the 70s, the world’s best runners had to scrimp & save to live as an amateur athlete. Amateur status was restrictive: no coaching, receiving money or free shoes or apparel from companies. Steve Prefontaine, legend of the sport, famously told the NYT in 1974 that if he competed in the Olympics, he would be doing so as a poor man.

Fast forward to 2014. There's a little more money in the sport. The running boom of the 80s had happened. Nike made running cool. But, similar to cycling, running apparel was daggy. Frumpy. Neon. Not fit for public consumption. Much like Rapha and the plight of MAMILs (middle aged men in lycra).

Tracksmith’s founders, Puma exec Matt Taylor and Rapha creative director Luke Scheybeler took the heritage of running, repackaged it and sold it. Their audience: ‘the running class,’ or “the non-professional yet competitive runners dedicated to the pursuit of personal excellence.” Let it be said that Tracksmith’s running class probably have quite well paying jobs (you’d need to in order to afford a $68 running singlet).

But brands don’t grow on clever positioning alone.

Where Tracksmith shines: brand behavior and creative execution.

The strategy: Behave like a running club, not a retailer

Tracksmith doesn’t behave like a retailer.

Tracksmith behaves like a running club.

In founder, Matt Taylor’s words👇:

"In high school and college, running cross country or track can have a very strong team component...But as we graduate into the real world, we often lose that team connection and instead view running as an individual pursuit: the loneliness of the long distance runner.

What Tracksmith masters: bottling the ethos of a serious long distance runner, and then dramatizing it.

In a world that’s bombarded with short form sales messages and out to make a quick buck, Tracksmith opts for long-form storytelling and a brand that endures.

I want Tracksmith to be around for 100 years. And unfortunately — or, actually, fortunately — you can’t buy authenticity or credibility. Instead, they’re earned over a long period of time with consistent, sustained efforts. So although we do spend some money on tactics that have an immediate return, we’re more committed to the little things that don’t, but that do pay dividends establishing a connection with our customers and instilling our brand values in a way that will continue to resonate. You can’t do that with a Facebook ad. - Matt Taylor, Tracksmith founder

Brand marketing: Demand gen, but make it cinematic

Tracksmith creates demand through beautiful long form stories glorifying long distance running. Tracksmith has 56 videos on its YouTube channel and 7680 subscribers (compare to Janji, with 50 videos and 214 subscribers). If you’re a brand and people are subscribing to your YouTube channel - you are doing something right.

Tracksmith’s stories are beautiful, poetic, and distinctive. Importantly - they sets the stage for its product - and it’s wearer - to be the hero in its films, broadsheets, and interactive digital spreads.

Why this is clever: quality work will find its audience. What you want is what the print industry calls “passalong rate” - something that’s good enough to pass along to someone else who’s also in the target audience.

The lesson: if you have great stories to share, don't shortchange yourself.

Tracksmith honors the weekly long run with The Church of the Long Run, a beautifully shot film that follows a runner’s weekly long run in real time

The reason Tracksmith gets their people? They are runners. They’ve built their brand around the rituals and rhythms of a long distance runner.

Tracksmith is very obviously a brand built by runners, for runners, and it shows.

Brand operating system: Building belief from the inside out

Tracksmith does this from its physical spaces to its employees to how it invests its sponsorship dollars.

Here’s how they do it:

Make bricks & mortar shops a shrine to running culture. The shops features photos of runners on the walls, paraphernalia throughout the store. Tracksmith invited Roberta Gibbs, the first woman to run the Boston Marathon (now a sculptor), to display her work in Tracksmith’s space.

Hires devotees of the mission. Tracksmith hires runners. Former Tracksmith’s accountant Jason Ayr covered the 340 miles between LA to Las Vegas entirely solo, documented on film in Alone, Together.

Put your money where your mouth is. Building a brand is as much about what you will do as what you won’t do. Tracksmith is proudly for the amateur athlete, and they’ve operationalized that belief by deciding not to sponsor any professional athletes, instead funding aspirational amateurs. In the February 2020 Olympic trials, a whopping 120 of 500 starters were wearing Tracksmith.

Building a brand for a community to buy into

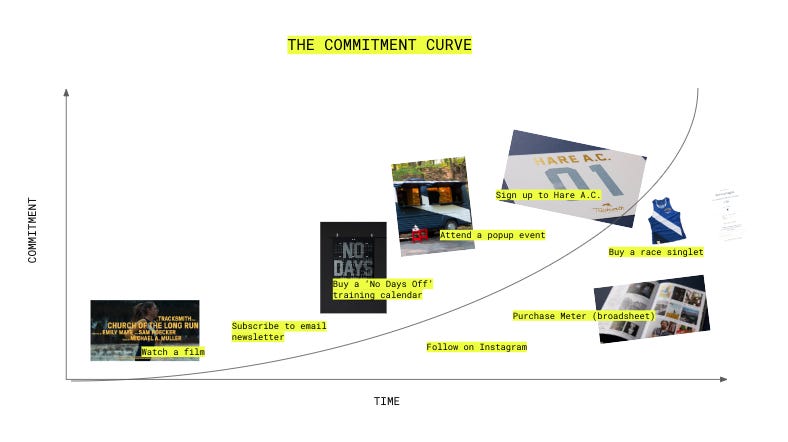

There’s a concept in community building called the commitment curve: it’s a tool for visualizing how people buy into a movement and become part of it.

Tracksmith build the shared experiences in running culture into their brand.

It’s important to remind people about those shared experiences that make the sport so much richer. We do that through our community, Hare A.C., but also with the workouts and events we offer at the Trackhouse in Boston. It’s also something we bring to our pop-ups at the major marathons – whether that’s hosting a group shakeout run or hand-stamping finisher’s posters after the race. There’s an incredible sense of camaraderie that comes from having a shared goal of running faster. As a brand, we understand that these human connections are what keep people coming back.

For a brand like Tracksmith, the commitment curve might look something like this:

In a commitment curve, you’re working towards a goal - let’s say Tracksmith’s is to build the world’s largest amateur running club. The commitment curve illustrates what asks to make, when.

Douglas Atkin used this strategy at Meetup and Airbnb to build movements of people more powerful than a single paid employee or even a small army of volunteers could do. Atkins advice:

“Lower the barrier to entry with low barrier asks and gradually ramp people up the commitment curve with incrementally harder asks that get incrementally more commitment and generate incrementally more reward.”

That means not asking a first time website visitor to sign up for an annual membership to a running club they’ve never heard of. Ease in, ya know?

Tracksmith has united a serious band of runners and it’s building a valuable brand that can go the distance, and it’s paying off.

💸 How brand builds Tracksmith’s bottom line

Price: Varies, $68 for a singlet, $128 for a pair of pants

Generating revenue? Yes

Since March of 2022, 98% of sales have been online

Between 2019 to 2022, sales increased 280%

Overheard: ““People love this brand. They are rabidly loyal. Because they see that it’s made for them.” Elliot Conway, Pentland Group

Investor line up: Causeway Media Partners (investors in Zwift), Pentland Group, Founders First, FJ Labs, Jeremy Levine, Jordan Fliegel

Publicly traded: No

YOUR TURN

🛠️ Takeaways & tactics to love & learn from

Find the poetry in what you do. There is magic and poetry in some aspect of your business that people feel is sacred. If you’re not the target, find the people who are & then write in their voice.

➡️ Tactic: Get your manifesto on & write an ode to your target audience. Need a thoughtstarter? Copy & paste Tracksmith’s manifesto into ChatGPT and ask it to write one for you (I call this trick the SFD - s****y first draft).

Give people ways to participate. Give people who find their way into your world more ways to participate.

➡️ Tactic: Map your own community commitment curve. Find the ‘believers’ who are willing to take those actions and convince them to try it.

Director’s cut: glorify the world your product exists in. Rapha, and Tracksmith do this brilliantly. Tracksmith glorify a lifestyle and way of being that surround the product.

➡️ Tactic: Pick a film director that embodies your brand style. Imagine they’re directing a mood film for your brand. Write the brief, with references.

Thanks for reading. Got a brand you want to see a deep dive on? Leave a comment or slide into my DMs.

If you thought of someone when reading this, you would be the coolest if you forwarded it to them.

As they say, sharing is caring.

👋 Until next time,

Amanda

Very interesting analysis of how Tracksmith has grown in the last decade. Thanks for writing this.